SMALL STEPS AND GIANT LEAPS: THE QUEST TO SHAPE A POST-PANDEMIC CHURCH

It’s never been more important to keep up with the news today, and it’s never been more depressing. We have to know about a constantly changing set of rules that are so intimate in their application that at any other time you’d be forgiven for thinking we had slipped into a totalitarian nightmare. If we had known, when the Prime Minister first said ‘you must stay at home’ in March 2020, that we would still be staying at home in February 2021, I shudder to think how it would have been received. And yet here we are.

When we stumble through a trauma, dazed and bewildered, we rarely think about the longer term – it’s just too much. The football manager’s cliché about taking one game at a time kicks in. One day, maybe one week, is enough. But there is a larger picture.

The current health emergency has been running in parallel with an emerging economic crisis, but in time it will give way to it. Like the terrible blast in the port of Beirut last year, where the first explosion was followed by a second shockwave that blew people off their feet, the health crisis will be overtaken by an economic one.

In helping churches address the emerging new realities, we need to get to grips first with the national picture. If Covid has been a disrupter, then in the longer term it may be an amplifier. Social and political divides may widen. Those who were poor will be poorer still; those who are rich will get richer still. The richest will become unimaginably rich. But the middle classes, which our churches are full of, are not exempt, and new realities will dawn on them too. The robotics economy will expand, being as unstoppable in its own way as the Terminator, and it will take white collar jobs as well as blue collar jobs with it. This influences politics. In the 2016 US Presidential election, Donald Trump made the largest gains in those communities where robots had been adopted most extensively.

The architecture that the digital giants have constructed is fundamentally flawed. If you get the chance, watch The Social Dilemma on Netflix to see this. Polarisation will only increase, setting one tribe against another. Brexit has been followed by Covid, which will be followed by something else. And each story messes with our heads. False stories spread six times more quickly than true ones via the internet.

There are other trends to think about but I have highlighted these to show that the crisis we are living through will continue to be a crisis for many years to come for lots of people. It’s so easy to think that when we’re OK, others must be too. But this is not how recessions work. Around us, some people are drowning in despair. The culture is evolving in rapid and unpredictable ways that calls for an astute, prophetic voice. A voice to be heard in society and in the Church itself.

Our first steps into this new world will be as small and tentative as everyone else’s. In trying to map the terrain, I’m suggesting a simple template for churches: the 3Rs. Recovery. Reimagination. Reach. They are not exclusive categories, nor are they sequential. They are entwined. But they do each have properties and I want to set out some of them today.

Let’s start with recovery - and with us personally. There’s a lot we may not have figured out because our emotions are complicated. The chances are some of these emotions lie near the surface, in the way tears come more easily or anger flares more readily. We can be sure others feel the same. And habits will have changed. We may not have intended these new habits, but some will be good for us.

Lockdown has felt like wading through treacle for most, but there may be a better rhythm to how some live. Rested people are more creative, and able to hear and see things they can’t when exhausted. The tech consultant Alex Soojung-Kim Pang worked crazy hours in Silicon Valley start-ups and was converted to the cause of rest, set out in his book Rest: Why You Get More Done When You Work Less. Rested people are less risk averse. We need a culture of appropriate risk taking, especially in a world that has been tipped upside down. So how do we model a sabbath rhythm for others?

It’s said the hardest thing in leadership is to do nothing. We feel the pressure to be doing something – and to be seen doing it. Activist models of leadership have us running fast, to stay ahead of the game. But in 2021 we should hit the ground listening. We are emerging into the open air after an earthquake. All around us, the world has been shaken and buildings have been razed to the floor. The instinctive response is to run to the first piece of rubble we find to try and lift it. The smart thing to do is to walk around and take in the scene. To listen carefully for the quiet cries for help that lie beneath some masonry, to call for assistance, and then to start lifting. We should spend more time than is comfortable listening for these voices. Everyone has a story to tell about the pandemic, but some have lost out much more than others. These are the people we should find and devote our pastoral care on.

For months we’ve been trying to make sense of our viewing figures online and there is much to interpret. But there is another partially hidden cohort, and this is the number who have opted out of any kind of involvement in church in the last year. We all know that part of the reason for the decline in regular worshippers over the years is because we have leaked people via the back door. While getting enthusiastic about the ten people who joined us in any one period, we neglect the fifteen who slowly filed out of church and were never followed up. There is a serious risk we will lose more people this year than previous years, because households have developed different habits of life through the pandemic. Early, focussed pastoral attention on the people who are drifting away is essential if we are to recover well.

And determining the size of our volunteer base is a key task before we go running into new ventures. Some of our super volunteers, those who do everything, may have decided they want to do less now – who can blame them? But there will be people wanting to volunteer for the first time. Some of these may wish to join us from the wider community, especially if it’s in social action. We should also see people’s volunteer time in other local projects as an expression of their faith in Jesus and not resent them for not being available for church-centred work. This is where recovery morphs into the reimagination of church.

Ivan Krastev, author of a long essay on the political outcomes of the pandemic says: The world will be transformed not because our societies want change or because there’s a consensus for the direction of change – but because we cannot go back.

The geographer, Jared Diamond, added to this when he said the task for bodies is: to figure out which parts of their identity are already functioning well and don’t need changing and which parts are no longer working and do need changing.

There will be pressure for churches to return to what was before. I get that. There is a longing for a return to normality and we want people to return to their churches to find in them the old sources of comfort and reassurance. This is part of our recovery. But the evidence from those who study major crises is that our institutions will not be the same and we should adapt to this. The world we’d like to return to no longer exists in its old form.

How we understand this reimagination is key and it will have different iterations in each church and community.

Right now, most people are exhausted from the experience of the last year. The house arrest. The constantly changing rules. The lack of family and friends. The loss of touch. The absence of spontaneity. The anxiety and fear. There has been illness, bereavement, loneliness, mental illness, lost schooling, furlough on reduced pay, redundancy. Our horizons have contracted as the whole population simulated the experience of growing very old, when life narrows and going out becomes harder until you don’t really want to do it.

The worst thing we could do right now is a season of megaphone preaching where we tell people, repeatedly, that this year is a not to be missed fantastic opportunity for change we must grasp with both hands. That we just have to work that bit harder for the Lord to make the breakthrough and all will be well. I’m guessing not all those returning from Israel’s exile wanted to be frantically re-building the walls and enforcing the covenant with the activism and relish of Nehemiah. I suspect we would have some sympathy with them. That’s why a good recovery is essential for the longer term re-imagining of the Church.

But there is another factor, which complicates things. There is usually only a limited period of time in which to make changes coming out of a crisis, before the window closes and it becomes harder to open it again. I do not know what this time frame is and, in any case, it will be different in each place. But we should know it exists. Getting the timing right between taking the deep breaths of recovery and making the plunge into the waters of change is going to be very hard and deeply important.

Perhaps the first place to start is a reassessment of existing projects and commitments in the light of the people and resources that remain to us. The Church of England believes in death and resurrection but frequently practises life support. In almost every parish there are things – events, committees, services – you can name them – that are kept alive because we don’t want to offend people. Sometimes things have to die in order that there might be new life.

To build up momentum, we need to listen to those stories I started with and to assess the new shape of community need. Our learning and social action should be realigned. The Growing Good report by Hannah Rich for Theos and CUF has been well-timed. It shows the virtuous links that exists between church growth, social action and discipleship. Meeting human need is walking the way of Christ and many people who join us from outside, just wanting to help, soon find the risen Jesus of Emmaus sidling up for a chat. Millennials in particular value a hands-on faith that makes a tangible difference in the lives of others.

The Church responded well to the last decade of social welfare budget cuts, stepping in alongside other agencies to meet need. It’s in our spiritual DNA. But perhaps because it is so instinctive, we don’t always reflect on how it makes the kingdom of God draw nearer in the lives of all involved and how it fits with other parts of our mission.

While churches have been good at social action, we have not always been as clear in saying why we do it. We are not to show off when we care for others – Jesus was clear about that, as our Ash Wednesday readings reminded us. But we are expected to have a reason for the hope that is in us. And it’s this reason that should be a part of our reimagination. Great emphasis is placed on personal experience today, which sits well with the power of personal Christian testimony. But the world is rapidly filling up with people who assert: it’s true because I say so. The growing conspiracist agenda is built on this and we must distinguish our faith from it, because in parts of the world it has become tangled up with it like a net. There is an evidence trail in the Gospel that has led so many to faith. A knowledge of, and ability to debate this evidence should not be the preserve of experts; it should be the lifeblood of the Church.

We know that church will feel more hybrid in future. There will be face to face encounters, and there will be digital. Not every church has the capacity or desire to pursue a hybrid agenda, and should not be stigmatised for this. Others will develop their offer as they begin to understand their audience. A generation raised with screens will be grateful for online support and learning. Shutting churches, however briefly in historical terms, has served the cause of 24/7 faith. We must welcome this vision and pursue it. But there will be more people who choose to go it alone now. We already have a section of the population that claims faith but doesn’t share in it with others. The digital is here to stay but should not dictate to us.

There is a weight of pre-pandemic research that shows the greater benefit to people of face to face meetings over screen mediated ones. MIT Professor Sherry Turkle heads this field with her books Alone Together and Reclaiming Conversation. There is something profoundly healing and encouraging about being in the presence of another person. We all know our faith is best pursued with others; that even in the highly communal early Church people were being tempted to give up on meeting with others and were advised not to. As we gravitate to screens, there is something of a prophetic witness to be made round the value of public gatherings.

Talk of this leaks into the third R: reach.

The sociologist Ray Oldenburg speaks of third places that are neither home nor work but gathering spaces for people from different social backgrounds who can form bonds and exchange ideas. It sounds like church, but few people see us this way. Fairly or not, we are sometimes perceived like a castle that has drawn up its bridge.

The pandemic has been especially hard on lonely people and expanded their numbers so much that we may be faced with a new pandemic of loneliness. How we use the buildings we have to foster social inclusion is an audit to be made. We assume older people suffer the most, but statistics show young people to be as lonely, if not lonelier. Harvard Divinity School’s study How We Gather shows that millennials are joining organisations that blend a sense of community, self-awareness and a resemblance of religion. The authors say ‘these are communities that are helping people to aspire towards goals, transform themselves and work towards change while holding each other accountable to make things better.

Sounds familiar?

Church sponsored community hubs create a place for friendship and a range of agencies and services to come together in one space to offer advice and support. Coming out of this pandemic, people will need mental health support, advice on housing, jobs and benefits, support in caring duties. When you are distressed and trying to find your way round the system on the phone but can’t get beyond automated voices, it can be deeply isolating. Far better to engage with people face to face in one place. In any local community, it is often the church that has the plant to deliver this, to connect human need to practical support and be at the heart of the services offered.

Work is also being re-shaped. Fewer people will commute into cities every day of the week. This may hollow out city centres, which is a major policy issue in itself. As people work at home more frequently in future, it will create a need for new local connections because, as we have seen, working from home can be cramped and isolating. Innovative local responses to this will be part of our reach.

I’d like to finish with these observations. The Oxford historian Margaret Macmillan says it is the mark of a nation how well it subsequently cares for the greatest losers from a crisis. The same is surely true of the Church. Who have been the losers in your community? In wider terms, older people have lost out in the health crisis, especially in our care homes. But in the coming economic crisis, it is young people who will lose by far the most, with impaired life chances and national debt mushrooming like a nuclear cloud.

Lockdown made life appalling where there is domestic violence and abuse. The precariat is growing. People who juggle several jobs at once, on zero hours contracts, living in insecure housing, who are monitored and rated on their performance by people who don’t care about them. What does good news look like for them? We know we have lost touch with young people. But we have also lost touch with the precariat. Not everywhere, of course. There are shining examples of Christian care for the economically vulnerable. But if church life itself is anything to go by, the precariat are not present and we do not shape our life around their precariousness.

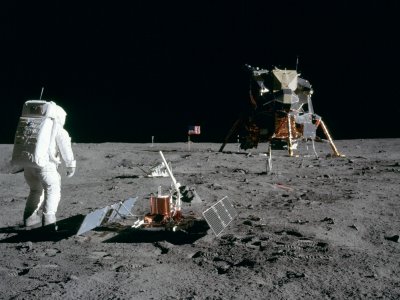

It was, of course, Neil Armstrong who said the first foot on the moon was a small step for a man, but a giant leap for mankind. Sometimes a small step for the kingdom of God feels like a giant leap for the local church, and one it doesn’t have the courage to make. But ours is a God of paradox. Sometimes that one small step for the local church turns out to be a giant leap for the kingdom of God.

Right now, that’s the smart intercession to make.

POPULAR ARTICLES

Obama's Covert Wars

The use of drones is going to change warfare out of all recognition in the next decades.

Through A Glass Starkly

Images of traumatic incidents caught on mobile phone can be put to remarkable effect.

What Are British Values?

Is there a British identity and if so, what has shaped the values and institutions that form it?